Breakfast in the Walsh Household

The Headhunters

Irish Independent, Weekend Magazine, Saturday 28 April 2012

(© Ciaran Walsh, 2012, Word count 1,500)

It takes about two weeks to

preserve a brain inside a severed human head. First you remove the head and

then you pump preservatives through the carotids, repeating the procedure until

the brain is sufficiently hardened to allow work to commence. This is the short

version. A detailed and altogether more gruesome description is contained in

the Cunningham Memoirs in the library of the The Royal Irish Academy.

The work in question is an

investigation into the difference between man (europeans and negroes) and anthropoid apes (orangs and gibbons).

This was happening in Dublin in 1886 in the

Anatomy Department of Trinity College Dublin.

Cunningham was professor of

Anatomy and Surgery between 1883 and 1903. He was investigating the origin of

the human species in the aftermath of an intensely political and religious

struggle that ended, sort of, with the triumph of evolutionary theory.

The human head was the

focus of a lot of attention. A report from 1906 describes a meeting of the

Ethnological Society in York where a table was laden with skulls that the

ladies, several of whom were present it was noted, ‘handled with as little

trepidation as they would a water melon.’

Size mattered ...

enormously. Cranial capacity – brain size - was regarded as one of

the main things that separated humans from anthropoid apes. Cunningham was

digging deep to find out exactly why. While Cunningham stayed in the

lab, others went out into the field. Anatomical evolution represented one part

of anthropological investigation. The development of human societies

represented another and a lot of time was spent gathering information on other

– non white Anglo Saxon – people that the empire had gathered up in the

commonwealth, the so-called savages.

Ireland was a special case.

How did one explain the presence of a primitive (white) race living in the back

yard of the United Kingdom? The answer had to lie in the origin of the species,

in this case the Irish peasant in remote communities all along the west coast. The Victorians began to search for

evidence that might explain the existence of the ‘black’ or ‘Africanoid’ Irish.

Justin Carville specialises

in the connection between ethnography, photography and the representation of

Irishness. He points to the jutting lower jaw of the Irish as the principal

evidence used to suggest a link between Irish primitives and, ultimately,

anthropoid apes.

Being Victorian, the

scientific community needed something more ‘scientific’ in terms of proof. So,

like good ethnographers, they set about collecting information on the physical

characteristics and customs of the native Irish. Cranial capacity was high on

the agenda. Enter the head hunters.

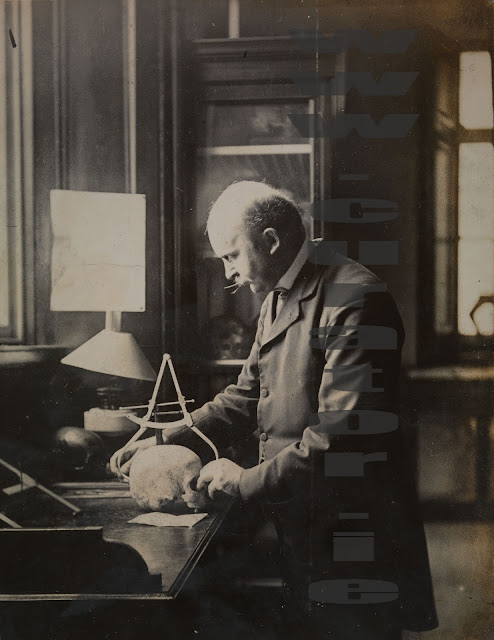

© Trinity College Dublin

Cunningham had a young

assistant called Charles R. Browne. He had entered Trinity in 1885 and was

studying medicine. They were joined by Alfred Cort Haddon, a zoologist who had

developed an interest in ethography following an 1888 expedition to the Torres

Strait Islands just north of Australia.

In 1891 they persuaded the Provost

and Senior Fellows in Trinity to make part of the Museum of Comparative Anatomy

available for an Anthropometry Laboratory. It was equipped with a grant from

the Royal Irish Academy. The plan was to transfer the laboratory during the

‘long vacation’ to a carefully selected district in order to carry out an

ethnographical survey of the physical characters and habits of the inhabitants

as a way of ‘giving assistance to the anthropologist in his endeavours to

unravel the tangled skein of the so-called Irish race.’

In 1893 Haddon and Browne ‘pitched

their tent’ in Aran and set about recording the eye colour, skin pigmentation and, of course, cranial

capacity of anyone they could get their hands on. The idea that

the ‘Aranites’ might be traced to an ancient race of ‘Firbolgs’ had, no doubt,

influenced the decision to go there.

The whole

thing was photographed, photography being regarded as an essential part of the

anthropometrists kit along with the Travellers Anthropometer, the compas d’épaisseur,

the compas glissière and the index of Nigressence, a complex

formula for determining the ‘blackness’ of a subject.

They took more than

measurements and photographs however. When they could they collected the skulls

of dead islanders and lodged them in the musuem in Trinity, the collection of

specimens being an integral part of the way they worked.

In 1893, Browne recorded that

“In addition to the observations made on the living subject , the measurements

of a series of crania, the first ever put in the record from this island

(Inisbofin) were obtained at St. Colman’s Church, in Knock townland. As they

could not be removed at the time of my first visit, I was forced to measure

them on the spot, and, as it turned out afterwards, it was well that this

precaution had been taken, as, in revisiting the place some time after, I found

that they had all disappeared, having in the meantime been removed to some

place of concealment.”

Haddon and Browne published a

written report of their research – an ethnography – in 1893. This was ground

breaking stuff and Haddon was getting noticed. In 1893 he moved back to

Cambridge and led an expedition to Torres in 1898. He gained a reputation as a

pioneering and influential ethnographer. He also became known as Haddon ‘the

Head Hunter.’

Browne remained in Dublin. He set

up a general practice in 66 Harcourt St. but continued his involvement in

Anthropology in association with Cunningham. He is remembered primarily through

his involvement with Haddon in Aran, a mere footnote in the development of Anthropology

in Britain.

It is not widely known that Browne

continued with his surveys - and his headhunting - throughout the 1890s. In

1889 he reported to the Royal Irish Academy he had surveyed Inishbofin and

Inishark, The Mullet, Iniskea, Portacloy, Ballycroy, Clare Island and

Inishturk. He went on to survey Garumna and Lettermullen in 1898 and Carna and

Mweenish, Connemara in1900.

He carried out a photographic

survey of Dun Chaoin in 1897 but no evidence of an ethnography has been found,

whether it was written or not. In 1903 funding was sought from the Royal Irish

Academy to carry out an ethnographic survey of Donegal but it does not appear

to have taken place.

After that Browne disappears from

the record. He went to England where he was appointed as a Surgeon Lieutenant

of the Gloucestershire Regiment in October 1904. His death in 1931 was recorded

by the Royal Irish Academy.

In 1997 a very elderly lady,

Browne’s daughter, donated six photographic albums to the Library in Trinity.

They contained a remarkable collection of photographs documenting the work of

the Anthropometry Laboratory and the ethnographic surveys of the west coast of

Ireland.

These photographs had never been

published, apart from a small number that were included in the proceedings of

the Royal Irish Academy in the 1890s. They are remarkable for two reasons: as a

collective portrait of the people of the west coast of Ireland and, as a record

of the development of social documentary photography in the 1890s.

In 1895 Browne was in Mayo. He was having difficulty

taking photographs in the wind and rain but he still managed to get “17

portraits, 14 of them individuals measured, 12 groups, taken in all parts of

the district, 30 illustrations of the occupations, modes of transport, and habitations

of the people, also several of the antiquities of the district, and a set of

views showing surface of land and nature of coastline, etc.

Some of these photographs

were taken by myself, others by my brother J. M. Browne. The addition of the hand camera to our

appliances has proved to be a great advantage, enabling portraits of unwilling

subject to be taken, and adding to the value of the photographs of occupations

by admitting of their being taken when the performers were in motion. It could also

be used when the high winds would not allow the setting up of a tripod stand.”

A selection of these

photographs will go on exhibition in association with the Library in Trinity

College Dublin and supported financially by the Office of Public Works (OPW)

and the Heritage Council. It opens on Thursday 3 May 2012 in the Blasket Centre

in Dun Chaoin, West Kerry where it will be on show until the end of June. After

that it goes on the road, travelling to Aran, Connemara and the Museum of

Country life in Mayo, all the places Browne surveyed.

It is one of the most

important photographic archives to come into the public domain in a long time;

Browne has named many of the people in the photographs, a fact that sets them

apart from every other archive.

And there is more. The

ethnographies are full of detailed descriptions of the lives of the people of the west of Ireland. The devil is

in the detail and Browne’s observations are incredibly evocative. He tells us,

for instance, that the amount

of potatoes and fish in the diet of islanders combined with ‘the abuse of tea’

seemed to result in a lot of flatulence and constipation.

Elsewhere

he remarks that ‘The people on the whole are good-looking, especially when young;

many of the girls and young women are very handsome, but they appear to age

rapidly and early become wrinkled.’ Hardly surprising given

that ‘Whatever

may be said of the people of other western districts, the people of these

islands are not idle or lazy. They could not live if they were, as life is one

long struggle to them.” It seems the Irish Headhunter had a heart after all.

‘Charles R. Browne,

The Irish Headhunter’ opens in the Blasket Centre, Dún Chaoin west of Dingle on

Thursday 3 May 2012. Information available on 066 9156444 or on www.curator.ie.

No comments:

Post a Comment